If Precious, a film that earned an Oscar and a few more nominations because of its visceral portrayal of poverty and disenfranchisement, is your first film, then it only seems fitting that a similar grit and grunginess work its way into your subsequent films. Lee Daniels is not lost on this concept. However, his second film, The Paperboy, seems to be befuddled because of it.

Once again, and I say this as a positive, Daniels adapts a novel that tackles racial tension. This time, there is no Mary, the figuratively and literally beaten down mother from Precious who chooses to castigate her daughter for getting raped rather than the man who raped her. Mo’ Nique’s stellar performance brought this character to a scary, horrifying life and thus centered the gravity of the film. However, The Paperboy offers a life in the South where integration has become the legal precedent, but the racist culture and practices shines through this diaphanous revolution toward equality.

Anita Chester (Macy Gray) is the compensated house maid, but she’s still considered a slave by the elder Jansen (Scott Glenn) and his girlfriend Ellen (Nealla Guthrie).

His sons Jack and Ward (Zac Efron, Matthew McConaughey) are more progressive and, in general, more accepting of African Americans. Jack still lives at home and has a playful relationship with Anita; Ward is a star journalist with a Pulitzer Prize and Yardley, a black co-author (David Oyelowo).

But overall, The Paperboy is muddled, unsure of where to start and how to tackles a number of deep-seeded themes. It looks at generational gaps in racism: the older generation clinging to cultural norms while the younger sees room for acceptance — at least partially, if not in full (it is the South after all).

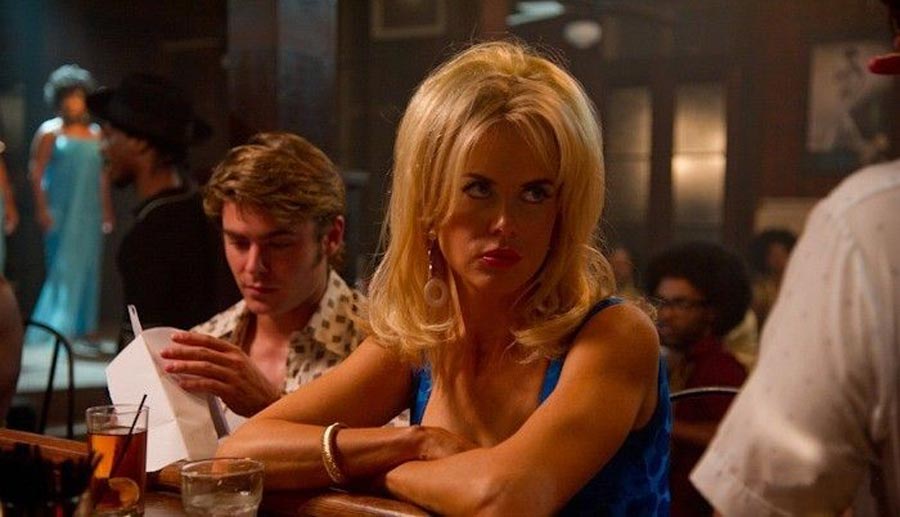

And then there’s the curious inclusion of Charlotte Bless (Nicole Kidman), a woman with a severe penchant – nay obsession – for incarcerated men. The dozens of men in prison she flirts with and seduces are represented by a equal number of letters pegged to a cork board. Like a child writing the land’s biggest rock star, she crosses her ankles and reads through their letters dreamily. She is at once a dominant woman, torturing those who have no recourse but masturbation, and one who wants to be dominated.

Which is where Hillary Van Wetter (John Cusack) enters the picture and connects Charlotte to the Jansens. Van Wetter is in prison for killing a local, well-known-racist Sherriff. Despite his white trash, desublimated exterior, Van Wetter professes his innocence, if inarticulately. Ward, the seeker of civil rights wants to help him break free to the prison system, and his only available connection to the “real Hillary” is through Charlotte, who soon kindles Jack’s affection and infatuation.

And then she pees on him.

But let me back up a little.

The odd co-mingling of the journalists, the dominant submissive siren, the young man infatuated with her, the black maid, the racist family, and the alleged murderer is a lot to tackle in the span of 100 minutes and very often dilutes any seriousness of the film. When Charlotte and Hillary first see each other in prison, accompanied by the Jansens and Yardley, the equivalent of phone sex occurs: Charlotte mimes fellatio, pretending to gag, and Hillary get aroused and, without actually touching himself, comes in his pants. Impressive.

However, there is no clear point to this scene in the grand scope of the film, which leads us back to the expectation that Daniels needs to be gritty – or at least the expectations that Daniels has of himself to be gritty. Sure, we see how rough Hillary can be, but isn’t this implied by his crimes? I’m not sure if alleged works after he’s been convicted, so until he’s exonerated, the crimes are his, no?

And sure, we get to see how open and controlling Charlotte is sexually. Sure, she is, I guess, the submissive one in this enactment, but she still gets to leave prison while Hillary has to walk around with semen in his shorts. But, in the end, it’s unclear why this scene matters.

Much like the scene in which Charlotte alleviates Jack’s jelly-fish-sting pain by shoving other young girls out of the way to urinate on him. To be clear, the other girls offered to pee on him, but Charlotte refused to let any “strangers piss on him.” Perhaps Friends or The Heartbreak Kid ruined the gravity of this scene for me, but it throughout, it felt as if the director just really wanted to relish in the presence of a golden shower.

Regardless of the reason, we are expected to believe that Charlotte’s actions are much less about being an analgesic and much more about marking her territory. This is all well and good in that it follows along with the above notion about her dominant side, but this act also convinces Jack that he’s hopelessly in love. He was merely infatuated before, but, like they say, the way to a man’s heart is through your urethra.

And then, if possible, the movie proceeds to get extremely convoluted, preachy, and incredible, in the most literal sense of the word. Precious was heavy handed, but Mary and Precious were its core. While the former was unlikable, she created a hard-to-deny-but-detestable sympathy. And the latter provided the underdog we wanted to root for.

The Paperboy doesn’t really have that. It has cultural norms, the castigation of the other, but it feels like a stew, disjointed and separate chunks, rather than a soup. I suppose this suggests that life is complicated and hardly ever smooth. At the same time, The Paperboy’s ethos more often boils down to, “well, shit, we’re all going to die in the end.”