As 2009 comes to a close, it’s time for the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences to award the producers who have sent out the most gift baskets in the last year with a tiny gold statue. And to improve on the mediocrity of nominations from 2008, this year the Academy has decided to sift through the hundreds of mediocre films to find ten highlyokay films that should be nominated for Best Picture. The legitimacy of this proposal is precarious inasmuch as the last decade of Best Picture winners were rarely the best picture, and some were plain silly.

From Lost, I’ve learned that you can’t change the past, so I don’t want to explore who did win and who should have won, but rather rank the last ten Best Picture winners.

(Note: The list includes pictures that received the Academy Award during this decade; thus, movies made in 2009 do not count because they will have received the award in 2010. We’ve all got deadlines people.)

10. Crash (2006)

Although a bit obscure, Cronenberg’s exploration of car-crash-inspired sexual fetishes that drastically alter each character’s life conveys the impact that celebrity death has on the individual psyche. Being the first film to win Best Picture with an NC-17 rating, Crash is carried superbly by Holly Hunter and James Spader, who—{editor taps me on shoulder}

Really? That convoluted piece of sanctimonious soapboxing? The one with the affluent, racist WASP who discovers that her Mexican maid is her best friend— or rather that it’s always a benefit to have a cell phone in your pocket in case you fall down the stairs like a septuagenarian woman?

The same one with the racist, sex-offender police officer who coincidentally happens by a car crash (clever) and decides to save the very same African-American woman whom he molested the night before in a routinely racially profiled traffic stop while he shows a rookie cop the ropes, which forces the same rookie cop to question his decision whether or not to join the force while ultimately kindling his desire to change the way that people look at the disconnected street of the melting pot of Los Angeles—except the Middle Easterners who still look a bit shady at the end since the token Arab attempts to shoot a blank through the head of the man whom he assumes broke into his pawn shop?

That’s unbelievable. No. Really. The story is completely unbelievable. On the other hand, it did gross more money than the movie about gay cowboys. {editor shrugs and leaves. I light a cigarette}

Well, Goldie Hawn won one too. Chew on that.

9. A Beautiful Mind (or, Please Give Me an Oscar So the Neighbor’s Young Son Stops Calling Me Opie) (2002)

Overall, the love story portion of A Beautiful Mind isn’t terrible, and if nothing else, the film is carried by solid performances by Russell Crowe, who probably should have won his second consecutive Oscar, and Jennifer Connelly, who collected her first Oscar. At the same time, the movie is fraudulent in that it creates an emotional appeal by suggesting that it is based on the life of mathematician John Nash, while in all facets, it is loosely based at best.

Nash is schizophrenic (this part they got correct). He didn’t have an imaginary roommate at Princeton. Nor did he believe he was working for the CIA.

With the CIA fallacy, Ron Howard takes the auteur complex—and the inherent audacity of diminishing the true genius and perseverance of a real person by marrying it to Hollywood masturbation— to a new level. The first attempt is valiant and even had me intrigued. However, once the audience discovers that Nash is in fact a schizophrenic and is not working for the CIA, Howard insists on wasting another twenty five minutes to lead us down the same path to the same revelation before succinctly wrapping up the fact that the actual John Nash learned to control his schizophrenia without medication—seemingly by walking up a set of steps at Princeton while aging one year for each step.

Final note: winners of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Science don’t give speeches while wives in poorly donned makeup look on. If James Frey became a pariah for placing “memoir” on a fabricated story, how did Howard and Grazer win an Oscar for doing the filmic equivalent?

8. Chicago (2003)

There’s really nothing wrong with this movie.

{Leaves momentarily to strangle a bear with dental floss. Returns wearing a shirt with “That’s Not a Gun in My Pocket” silkscreened on the front.}

Aesthetically, it’s stunning, and the acting is done by an accomplished cast. Even the story of treachery, deceit, and infidelity is well-told and encompasses themes that stretch from the classic to the contemporary.

The only thing holding it back on this list is the fact that it’s a musical. I have nothing against musicals, though for the genre to be successful, it should transcend that which is done without a chorus. In other words, being a musical doesn’t make this movie better or worse than a movie like Fatal Attraction or Double Indemnity (other Oscar-nominated films that visit the same theme). Music might make it entertaining, but Chicago revisits the same “music as spectacle” motif that 42nd Street offered in 1933.

Being the second musical nominated for Best Picture in two years (Moulin Rouge! was the first, but it lost to Fonzie’s little buddy from # 9) perhaps the academy was pressured to acknowledge the genre, though it’s difficult to see it as a better picture than The Pianist (hmmm…should a rapist get two Oscars in one year?) or The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers.

7. Slumdog Millionaire (2009)

Given that the murkiest part of the Great Recession occurred in 2008, perhaps Slumdog Millionaire was the cinematic dopamine that the American public needed to feel better about its economic plight. Why else would people go crazy for poverty porn?

While I was pretty psyched that I never had to wade through three feet of feces to get an autograph from my favorite actor, and it was refreshing to know that children in this country don’t have their eyes burned out so that they might be pimped out as singers on a street corner, these scenes of shock-value and corruption juxtaposed with a get-rich-quick game show serve to indict the Western World as the cause of this corruption. Clearly, there is validity in the “money as corruption” theme, but it’s done a bit heavy handedly.

As far-fetched as the story is, the scenery is beautifully shot in a variegated color scheme, and Danny Boyle showcases his prodigious directing talent, winning a much deserved Oscar—even if one should have come for Trainspotting. In the end, Slumdog is a touching, sentimental story of love that survives economic and social obstacles while it borders on wholly predictable and tear-jerker—until the inexplicable dance number at the end.

6. The Departed (2007)

Taken from the Hong Kong-based film Infernal Affairs, Martin Scorcese garners his first Oscar by revisiting the gritty gangster crime and loyalty that allure to youths in impoverished neighborhoods.

Apocalyptic note: Scorcese must have lost a bet with God: as of 2006, Eminem, Three Six Mafia, and Nicolas Cage each had an Oscar.

Strangely enough, this is probably one of Scorcese’s weaker films—and I know that Rotten Tomato enthusiasts are viewing the 92% rating and labeling me a hack, but The Departed would definitely have to fall behind Raging Bull, Goodfellas, Casino, The Aviator, and Cape Fear. This company does not make The Departed a bad film; there are plenty of memorable scenes that will keep the movie as a mainstay of gangster films—particularly Martin Sheen’s body plummeting off of the roof and the twist at the end that finds DiCaprio with a bullet in his right frontal lobe. While I’m not a huge fan of gratuitous twists (primarily because more often than not they become predictable elements rather than shocking revelations—see the “mute” kid inMystic River), I never thought Billy Costigan would get knocked off.

In addition to DiCaprio, the cast is replete with memorable performances by Alec Baldwin and Matt Damon— we even get a glimpse of the acting talent that Mark Wahlberg conveyed inBoogie Nights (then he starred in The Happening, so the jury is still out on the accuracy of Andy Samberg’s imitation. Right now it’s 7-5).

However, the movie loses a bit by way of Jack Nicholson’s performance. I know this seems rather sacrilegious since he has the most nominations of all time, and if you’re casting a crazy bastard as the lead crazy bastard, why wouldn’t Jack be your number one choice—but that’s precisely why his performance stymies the film: Nicholson has reached the point where he has become a caricature of himself and in turn Frank Costello becomes a cartoon character, not nearly as menacing or as creepy as Lewis’ Bill the Butcher or DeNiro’s Jimmy Conway.

Similarly, the film detours a bit toward cliché when Costigan, Sullivan, and police psychiatrist Madolyn form a love triangle; it’s not so much the love triangle that throws the story off (it serves as an adequate vehicle for Matt Damon’s fall at the end) but the bit where the audience is left to wonder whose child gestates in Madolyn’s womb is a bit, well, silly and unnecessary. And finally, what’s with the damn rats? I get the metaphor. Got it in the first scene. Didn’t need the CGI rat scurrying across the railing at the end. Now stop.

5. The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King (2004)

Aesthetically stunning and one of the best incorporations of CGI and live acting I had ever seen until this year’s release of Avatar. Not being a fan of the Fantasy genre, I was a bit skeptical when I sat to watch The Fellowship of the Ring, but I was soon drawn into Jackson’s imagining of Tolkien’s complex and intricate tale of Middle Earth. As a masterwork of technical achievement, the awesomeness of the film negates the last thirty minutes that could probably be pared away—having never read the novels, I was initially curious as to whether or not Frodo would perish, but soon became more indifferent and rather eager for the end credits. That said, Jackson also achieved something that few multi-film epics have: fashioning a solid nine hour film, neatly cut into three sections with a sufficient amount of anticipation that lures the viewer to the subsequent film and enough closure to keep the audience satisfied.

Likewise, Jackson does a solid job of conveying a tale that has an immense cult following, satisfying the consensus of Lord of the Rings junkies who agree that this series is a solid adaptation of Tolkien’s novels. (Note: by consensus I mean the four LOTR junkies I know—they all go to the same meetings right?) Clearly, the Best Picture Oscar was well-deserved, though the film still ranks in the middle of this list because the award symbolizes the culmination of the nine-hour-plus tale as opposed to the autonomy of this film.

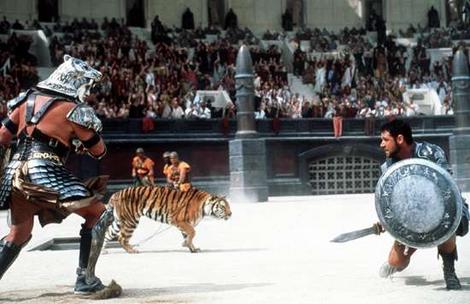

4. Gladiator (2001)

This might be the first solid CGI movie of the 21st century and a vehicle that leads to digital perfection found in The Lord of The Rings trilogy. Similarly, director Ridley Scott composes an epic battle in the beginning of the film that blends brutality and camera technique. Often, brutality becomes the focal point of a battle, sacrificing cinematography; however here, Scott inserts flashes of brutality on a chaotic and frenetic battlefield that has been shot at a slightly less than normal film speed, fashioning scenes that are sped up—though they avoid the hand-cam nausea that so many contemporary action films have adopted.

In the same vein, Gladiator never devolves to a movie driven by shock value. This is rather impressive given the revenge-tale premise. Even when Maximus finds his home torched and his wife and son murdered, the bodies are not shown (nor is their death); instead, the audience sees feet dangling at the top of the screen as Maximus approaches and caresses the soles of his son and wife, weeping before collapsing. While he later exposits that they were crucified, and Commodus suggest that Maximus’ wife was ravished multiple times, Gladiator doesn’t indulge in visible gratuity in an attempt to make the audience cringe.

Even though Gladiator is ostensibly a revenge tale, the film also comments on the public desire for violence in a civilized, democratic society. Likewise, it also questions whether or not violence can be eradicated if the system is ideally left to the people (while Marcus Aurelius wanted to leave Rome to the people, when Commodus reopened the coliseum, the people clamored for the sight of blood and death; thus, how probable is it for true democracy to reign unimpeded?).

Aside from the impressive visual effects, the cast deserves much of the credit for Gladiator’s success: Russell Crowe, who won a Best Actor Oscar for his portrayal of Maximus, is characteristically solid, and Joaquin Phoenix delivers his first stellar performance as the conniving Commodus. Likewise, the battles within the coliseum are well-fashioned and hearken back to classic scenes from Ben Hur and Spartacus.

3. Million Dollar Baby (2005)

It pains me to enjoy a film that was adapted by the same Paul Haggis who pedantically pennedCrash, but here it is at number three. And the reason is not the story—it becomes a bit heavy-handed at the end when the issue of euthanasia is weighed in context of eternal damnation. Had the story stuck with Frankie’s need to maintain a paternal relationship by selfishly keeping Maggie alive as opposed to ending her suffering, the movie probably would have maintained a consistent emotional appeal; instead, the introduction of God as judge sort of convolutes the father/daughter dynamic that was constructed through the whole film.

My primary reasons for placing Million Dollar Baby this high is because of the acting and the directing. The cast is stellar, garnering Oscars for Hillary Swank, Morgan Freeman, and a nomination for Clint Eastwood. The relationship between Swank’s Fitzgerald and Eastwood’s Dunn is believable because it begins precariously and builds slowly, which fosters space between the audience and characters. Showing indifference toward Fitzgerald, Dunn only acknowledges Fitzgerald’s potential when he has no one else to take under his wing. Similarly, it seems that he agrees to train her to get her out of the gym—originally having no intention of managing her, just providing her some pointers. This follows the Eastwood-curmudgeon mantra and allows Dunn to grow on the audience as opposed to throwing us into an overly saccharine tale. In addition, Freeman gives an Oscar-worthy performance and narrates the film with a slow eloquence.

Furthermore, the direction is stellar. At times, Eastwood is hit or miss and his films range from the good (Unforgiven, Letters From Iwo Jima) to the bad (Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil, Changeling) to the ugly (Flags of our Fathers, Mystic River). I know it’s a terrible pun; however, his best directorial results are in films that are linear and focus on the relationships between characters, dabbling on internalized pain and for the most part, avoiding flashbacks that create tangential tales and implausible twists and turns.

In the end, Million Dollar Baby avoids the latter and effectively focuses on the former.

2. American Beauty (2000)

Often mislabeled as a film about dirty-old-man fantasies, American Beauty explores the devolution of the collective family in the face of individual consumption and the acquisition of social status. I know that sounds deep and depressing, but that’s the genius behind the film. Had Allen Ball and Sam Mendes simply presented a blunt tale about the obliviousness of American society and its futility, I can’t imagine it would have been as highly regarded. Instead, this cynical theme is overlaid with comedic moments and is conveyed through solid performances by Kevin Spacey, who won his second Oscar, Annette Bening, who should have won, and Chris Cooper.

Regarding the nymphet fantasy, it’s important to note that Lester Birnam does not go as far as Humbert Humbert or Noah Cross, who both fulfill their sexual fantasies through statutory rape and incest, respectively. Instead, Lester recognizes the inappropriateness of the situation and retreats, re-embodying the father figure that he should be. This doesn’t necessarily redeem him or make him perfect, but it exposes human vulnerabilities that emerge in a world driven by socially-constructed expectation that suffocates personal desire. Plus, his deviation from social norms results in his murder, which should stifle any stigma about pedophilic fantasy. More on the notions of futility in American Beauty can be found here.

1. No Country for Old Men (2008)

For the last two years I have been trying to figure out how No Country for Old Men beat outThere Will Be Blood for Best Picture, and while I still believe that There Will Be Blood will go down as this generation’s Citizen Kane and has clearly positioned Daniel Day Lewis as a canonical actor, No Country for Old Men is flawless.

The story is compelling, and in Coen brothers-style, the film avoids exposition while providing glimpses of characters that are randomly thrust into uncontrollable circumstances. And the abject lack of control might be why the film has grown on me so much. Javier Barem, in an Oscar-winning performance, plays Anton Chighur, the embodiment of death and inevitability. Cold and calculating, he hardly exists and is never seen coming.

The Coens debunk the notion that Chighur is preternatural at the end when he is t-boned in a car crash and his forearm is split in two, but he represents the futility of over-analyzing life and assuming that salvation finds the just. The beauty in the storytelling—which needs to be ultimately credited to Cormac McCarthy—is that Chighur is unbiased, driven by morals and an agent of circumstance: he levies judgment upon those who live stagnantly (the gas station operator who “married into” his situation) and those who act impetuously (Llewelyn Moss).

Maintaining another Coen brothers’ trope, there is no real ending. Sheriff Ed Bell is accountable for the numerous dead bodies that litter his normally quiescent town, and Chighur absconds without leaving a trace of himself within the wake of carnage. The greatest trick the devil ever pulled was convincing the world he didn’t exist (by the way, that’s Baudelaire, not Keyser Soze).

At the same time, Coen films never end in cliffhangers, forcing the audience to decide what happens next; instead, the Coens have perfected the art of providing moments that are fascinating in that they are moments and don’t require further exposition. Did you ever really wonder the sex of Marge Gunderson’s child? What does Lebowski do the day after? Who was the mercenary biker in Raising Arizona? Does Harry Pfarrer ever build another dildo chair in Burn After Reading?

In the end, No Country ranks at number one on this list because it rose to the top in a year that was stocked with solid films. While much of the decade was lackluster, No Country was in the company of Michael Clayton (a film that is quite underrated), There Will Be Blood, Juno,Atonement, Rescue Dawn, Eastern Promises, and Charlie Wilson’s War.

And, none of the cowboys were gay.